Mapping the Blueprint of Life

Автор: foabs2025 Learning

Загружено: 2025-11-26

Просмотров: 1

Genome Mapping Concepts

Mapping the Genome

I. Introduction to Genomics and Genome Mapping

Genomics is the comprehensive study of entire genomes, including all genes, their nucleotide sequences, their organization, and how they interact within a species and with other species.

Genome mapping involves locating genes on each chromosome. This process is similar to assembling a large and complex puzzle, where pieces of information are gathered from multiple tools and analyses. The final maps resemble navigation maps—genetic maps provide the broad outline, while physical maps provide the finer details needed to form a complete picture of the genome.

II. Genetic Maps: The Big Picture

A genetic map illustrates genes and their approximate locations on a chromosome.

Key Features

Purpose:

To provide the overall framework or “outline” of the genome, much like a map showing major highways.

Basis of Measurement:

Distances are estimated based on recombination (crossing-over) frequencies during meiosis.

Method:

Genetic maps are developed using linkage analysis, which evaluates how often two genes are inherited together. Genes that are close together tend to show low recombination, while genes farther apart show higher recombination frequency.

Distance Rule:

The greater the physical distance between two genes, the more likely a recombination event will occur between them—resulting in a higher recombination frequency.

Markers Used:

Genetic maps rely on genetic markers, which are genes or DNA sequences that are inherited alongside a trait of interest.

Limitation:

Because genetic mapping relies entirely on natural recombination, it can be influenced by recombination hotspots (areas with high crossing-over) or coldspots (areas with little recombination), making the estimated distances less precise.

III. Physical Maps: The Detailed View

A physical map represents the actual physical distance between genes or genetic markers.

Key Features

Purpose:

To provide detailed information about specific chromosomal regions, comparable to a highly detailed street map.

Unit of Measurement:

Physical distance is measured in nucleotides or base pairs (bp).

Key Methods:

Physical maps are constructed using:

Cytogenetic mapping

Radiation hybrid mapping

Sequence mapping

Advantage of Radiation Hybrid Mapping:

This technique is not affected by natural variations in recombination rates, allowing more accurate positioning of markers.

Sequence Mapping:

Uses DNA sequencing technologies to determine precise distances in terms of exact base-pair numbers.

Markers Used:

A common marker is the Sequence-Tagged Site (STS)—a unique DNA sequence with a known chromosomal location.

IV. Key Genetic Markers (Polymorphisms)

A strong genetic marker exhibits polymorphism, meaning it shows variation among individuals in a population.

Types of commonly used genetic markers include:

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms (RFLPs):

Differences in DNA fragment patterns produced by restriction enzymes and analyzed using gel electrophoresis.

Variable Number of Tandem Repeats (VNTRs):

Repeated nucleotide sequences in non-coding regions, with the number of repeats differing among individuals.

Microsatellite Polymorphisms:

Very short repeated sequences—similar to VNTRs but with smaller repeat units.

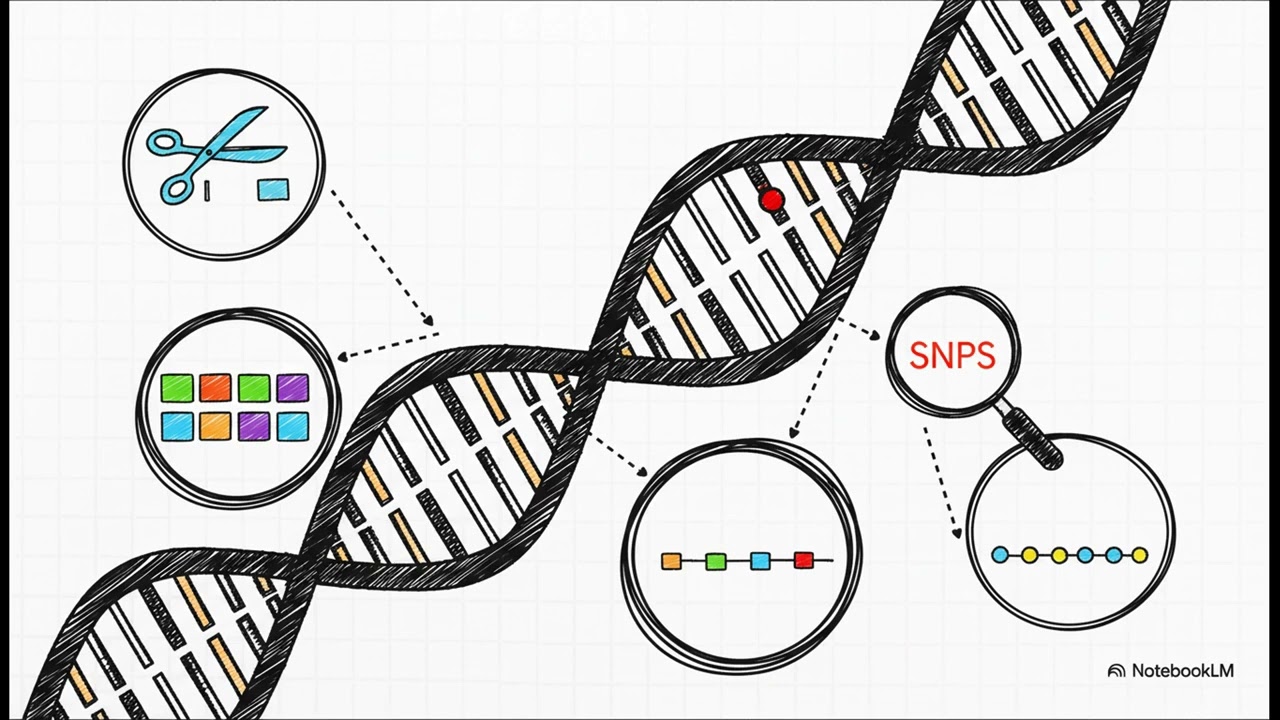

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs):

Variations occurring at a single nucleotide position within the genome.

V. Linking the Maps: Sequence-Tagged Sites (STSs)

STSs are essential for integrating genetic and physical maps. They provide consistent landmarks that can be identified across different mapping techniques.

Two widely used STSs include:

Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs):

Short sequences derived from complementary DNA (cDNA) that represent expressed genes.

Single Sequence Length Polymorphisms (SSLPs):

STSs originating from known genetic markers that help connect the broader genetic map with detailed physical maps.

Доступные форматы для скачивания:

Скачать видео mp4

-

Информация по загрузке: