Atomic Spectroscopy vs Molecular Spectroscopy | Atomic Absorption

Автор: Science with Dr. Akabirov

Загружено: 2025-11-16

Просмотров: 61

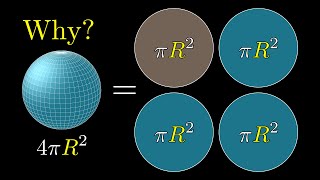

In this video, we’re going to explore an important distinction in analytical chemistry: the difference between atomic spectroscopy and molecular spectroscopy. Even though both techniques use light to study matter, the kinds of information they provide—and the principles behind them—are very different. Understanding this difference is essential for choosing the right technique for a chemical analysis. Let’s start with atomic spectroscopy. In atoms, electrons occupy well-defined orbitals such as s, p, d, and f. These energy levels are extremely sharp because atoms have no chemical bonds, no molecular vibrations, and no rotations. That means their transitions are purely electronic—electrons simply jump between these discrete orbital energies. So atomic spectroscopy examines the most fundamental electronic structure of elements, without any of the complexity of molecular bonding. Because these transitions are sharply defined, each atom absorbs and emits light at very specific wavelengths. This is why atomic spectra look like isolated, razor-thin lines—almost like the element’s barcode. These lines are so precise that even tiny concentrations of an element can be detected. Now let’s compare that to molecular spectroscopy. Molecules are more complex than atoms because they don’t just have electronic energy levels—they also vibrate and rotate. Every chemical bond behaves a bit like a tiny spring, and the entire molecule can rotate in space. These additional motions introduce many more allowed energy transitions. As a result, molecular spectra are typically broader, richer, and more structured than atomic spectra. Techniques like UV-Vis, infrared (IR) spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and fluorescence all fall under molecular spectroscopy. They allow us to probe different aspects of molecular structure: UV-Vis looks at electronic transitions, IR focuses on vibrational modes, and Raman gives us complementary vibrational information through scattering. Because these motions depend on the way atoms are connected, molecular spectroscopy tells us about functional groups, bonding, molecular shape, and chemical environment—things atomic spectroscopy cannot reveal. To understand how Atomic Spectroscopy works, I brought an example of Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy Instrument. Know that it’s important to first understand the heart of the instrument: the hollow cathode lamp. This lamp produces the very specific wavelengths of light that atoms will absorb. Let’s walk through how it works step by step. We start with the basic setup. Inside the lamp, there are two electrodes—an anode, which is positively charged, and a cathode, which is negatively charged. These are sealed inside a small glass tube that contains a low-pressure inert gas, usually argon or neon. The key detail is that the cathode is made from the same element you want to measure—sodium, copper, calcium, magnesium, and so on. Lets consider its Calcium. When we apply a voltage across the electrodes, the inert gas becomes ionized. For example, an argon atom can lose an electron and form a positive ion: Ar → Ar⁺ + e⁻ So now the inside of the lamp contains fast-moving electrons and positively charged argon ions. These charged particles start to accelerate toward the oppositely charged electrodes. The next step is called sputtering. The positively charged argon ions, Ar⁺, are attracted to the negative cathode. They strike it with enough energy to physically knock atoms off the cathode’s surface. These “knocked-off” atoms are atoms of the element we want to analyze—like Calcium atoms if the cathode is made of calcium. This process of ejecting atoms from the cathode surface is what we call sputtering. Now that these metal atoms are in the gas phase, they can collide with energetic electrons and other ions inside the lamp. Some of these collisions give the atoms enough energy to become excited, meaning their electrons jump to higher atomic orbitals. Excited atoms don’t stay excited for long. When they relax back down to their ground state, they release energy in the form of light, and here’s the key point: They emit light at very specific wavelengths that are unique to that element. Thats why they build a cathode tube source instead of shining any light. Now that we understand how the hollow cathode lamp creates the characteristic light, let’s shift to the sample side and look at what happens inside the flame before the light even reaches the detector. When your liquid sample is introduced into the flame chamber—usually through a nebulizer—it first gets converted into a fine aerosol mist. These tiny droplets are carried into the hot flame where several important processes happen in sequence. First, the droplets dry out. The solvent evaporates, leaving behind tiny solid particles of the dissolved analyte. As the particles move deeper into the flame, they experience even higher temperatures. This causes them to vaporize, forming gaseous molecules.

Доступные форматы для скачивания:

Скачать видео mp4

-

Информация по загрузке: